Orient-Abteilung / Oasis Settlements in Oman

This website was originally developed by Dr. Jutta Häser (until June 2008) and hosted on the servers of TFH/Beuth/BHT. Here you can see a reduced version.

Introduction

Oases are a particular strategy of human adaptation to a harsh environment which played a crucial role in the history of man on the Arabian Peninsula over the past five millennia. In the world of late 20th and the beginning of the early 21st century with its extraordinary industrial and technological developments oases with their agricultural basis have ceased to play their former role. Therefore, it is of great importance to document the old traditions and to investigate the possibilities of making use of the old settlements for tourism and other purposes, which have to be integrated into the overall development plans for Oman's oases.

Since 1999 an interdisciplinary project, entitled "Transformation Processes in Oasis Settlements in the Sultanate of Oman" was undertaken by orientalists, ethnologists, architects, urban planners, plant physiologists, computer specialists and archaeologists from the universities in Tübingen, Hohenheim, Kassel, Stuttgart and Muscat, as well as from the Orient Department of the German Institute of Archaeology in Berlin and with the financial support of the state of Baden-Württemberg, the Sultan Qaboos University in Muscat, the German Institute of Archaeology, and the German Research Foundation.

Study Area

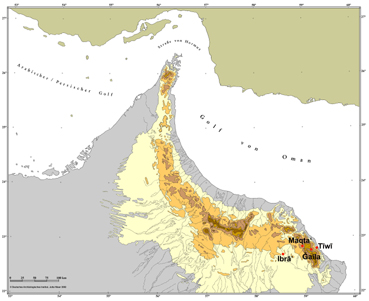

The study area of the second part of the archaeological reconnaissance stretches from Tiwi at the coast across the mountains of the the al-Hajar massiv to the oasis of Ibra at its south-western foot.

The focus of the Internet-Geoinformationsystem lies on the large oasis of Ibra. This area has not been archaeologicaly surveyed before.

Archaeological Methods

Various scientific methods were used for the archaeological survey of the area under study.

The survey has been prepared by studying a satellite image with a resolution of 1 m x 1 m. Many features could be recognised and were marked on the image.

Later, all of these points were visited during our field survey, and the different find spots were recorded with a Global Positioning System (GPS).

The satellite image was also used to draw up maps of the study area with the help of a special computer software. All archaeological sites have been marked on these maps.

Like in the other survey areas, most important was the collection of pottery sherds and other finds, for they are a great assistence in dating the ancient tombs and settlements. We scrutinize the sherds to find out the methods of production and exchange systems as well as the dating of the archaeological sites.

Preliminary Results

The examination of the satellite image led to the decision to start the survey on a hilly area between ‘Alayat Ibrā’ and Sufalat Ibra’. After the first inspection it became clear that this decision was right. Here the remains of an Umm an-Nar building of the 3rd millennium B.C. were discovered (I0004), which was shown by large boulders and scattered pottery. However, the walls are so dilapidated that the original appearance cannot be determined. Iron Age and Islamic pottery sherds show that the area was re-used in later periods.

About 200 m northeast, a large, round structure was found, which was probably an Umm an-Nar tomb according to its shape and the pottery in its surroundings (I0007). About fifty round and oblong stone structures were found on the same hill. Iron Age pottery and bones were found on two of the round structures. Therefore, we are probably dealing with an Iron Age cemetery. In any case, it is obvious that the stones of the Umm an-Nar tombs were re-used for the younger structures, and it is possible that there was more than one Umm an-Nar tomb.

An area of about 50 m x 50 m was bulldozed between these two small hills (I0005). In the gravel and sand heaps at the edges of this area, Wadi Suq pottery of the early 2nd millennium B.C. was found. A little south to it the surface was not yet bulldozed and some round underground structures were visible there. Presumably, a Wadi Suq cemetery with underground single graves was bulldozed at this place and only some graves remained. A rectangular stone structure, only one stone layer high, was recognizable on the ground close to the graves. No finds give a hint to function and dating.

During the survey in the palm gardens and the old towns in the oasis of ‘Alayat Ibra’ and Sufalat Ibra’, it turned out that this area was very disturbed by continuous use. In many cases the old surface is demolished by deepening the ground for the fields. Some small hills can be identified as remains of mud brick houses, which were scattered between the fields. Late Islamic pottery dates these remains. Few Iron Age sherds show that the area was already used during this period.

However,the main Iron Age occupation was located at two different sites. The early Iron Age settlement of the early 1st millennium B.C. was situated on a flat hill (I0039), which is now situated in an extended Islamic cemetery. No Islamic graves were built on that hill until today. Some very faint remains of walls are visible on the ground. However, the scattered sherds from early Iron Age settlement pottery made the occupation of the place obvious. At the foot of the hill and slightly apart from the Islamic graves, the remains of some early Iron Age tombs were found. However, it is possible and even probable that the Iron Age cemetery was larger in ancient times and that the tombs disappeared by the later use of that area as burial ground.

This settlement was not inhabited during the later part of the Iron Age. Instead, a new settlement was built on a high hill on the western side of Wadi Gharbi just above the old settlement of al-Qanatir (I0052). Thist settlement of the late 1st millennium B.C. respectively the early 1st millennium A.D. had already been discovered by the urban planners of the project group, when they mapped the architectural remains of al-Qanatir last autumn. The settlement consists of about twenty houses built with stone walls. In some cases the walls stand up to a height of 0.8 m. The scattered sherds can clearly be determined as late Iron Age settlement pottery. However, there are also sherds of early Iron Age grave wares. Therefore, it is obvious that the area was occupied by early Iron Age graves before the late Iron Age settlement was established.

Early as well as late Iron Age tombs were also found on the flanks of the hills extending on the southeastern side of Wadi Gharbi.

A settlement of middle and late Islamic date, i. e. from about 1055 to 1900, which was probably built already in the early Islamic period is situated on a hill above Wadi Gharbi (I0046). An old mosque is situated at the eastern slope of the hill and a small Islamic cemetery at the southern foot of this hill.

The survey in the modern built-up areas east of ‘Alayat Ibra’ and Sufalat Ibra’ showed that the hills were used for burials during the early Iron Age. However, these tombs are completely demolished. No other sites were recognized, and this makes clear that these areas were not used for habitation until modern times.

The survey was continued along the mountains on the eastern side of Wadi Ibra’ starting at Wadi Nam. At the junction of Wadi Nam with Wadi Ibra’ the hills were crowned by Hafit tombs of the late 4th or early 3rd millennium B.C. which mark the passage into the mountains. Further north several groups of different types of tombs ot probably 3rd millennium B.C. date were discovered. In all, more than 250 tombs were registered.

One type is similar to the tomb at Tawi Silaim, which was excaveted by de Cardi and Doe (Journal of Oman Studies 3/1, 18ff.). It consists of two to three double ringwalls and in many cases a plinth in front of the outer face of the tomb. The diameter of the tombs varies between 6 and 11 m. The chamber is about 1 to 2 m in diameter. Only few sherds of Umm an-Nar pottery were found. Other finds are beads of shell, carnelian and agate.

Another type of tomb is built like the first one but has a larger chamber with one or more division walls (for example I0419). In this respect they are very similar to Umm an-Nar tombs. In many cases one can find irregularly shaped limestones resembling the Umm an-Nar “sugar lumps”. Even if the limestoneused for the tombs at Ibra’ was not worked, it had a similar effect. Itcatches the attention through the sharp contrast against the dark brown stones used for the ring-walls of the tombs.

Only few finds were discovered. Some sherds of Umm an-Nar pottery, a fragment of a softstone vessel with dotted double circles, carnelian, agate and shell beads and frequently flint flakes were found on the tombs. In some cases also Iron Age finds were discovered, which show that the tombs were re-used during this period. For the time being it is difficult to determine if the finds of the Umm an-Nar period belong originally to the grave inventory or if they are the grave inventory of later burials. De Cardi and Doe state that they are not sure, whether the finds of the Umm an-Nar period in the excavated cairn 1 at Tawi Silaim belong to the original grave inventory or to a later burial. In the first case, the tomb would be older than the Umm an-Nar finds.

A third grave type are tombs with an outer double ringwall and two or more chambers inside the walls. In most cases they are situated on top of hills or on ridges, like the Hafit tombs. Since they are demolished in all cases, it is possible that these tombs were originally Hafit tombs. The inner ring-walls could have been removed and two or more chambers could have been built inside this extended chamber. Another possibility is that one or more tombs were built at the outer wall of an original Hafit tomb with the stones of the interior of this original tomb. Since only flint flakes were found inside the tombs, a dating is not possible at this moment.

Besides the paucity of finds, stone robbery is the other big problem which obscures the original appearance of the tombs. In many cases one could see traces of tyres on top of dilapidated tombs.

However, not only tombs of this early period were found. Remains of walls built of large boulders were recognized on three small hills close to different groups of tombs. In some cases rectangular structures of double walls were visible (I0267). The walls are only one to three layers high. There were no other finds than flint tools and flakes on these sites. Not a single sherd was found. At the moment it is difficult to date the structures, because the flints need a more detailed examination. However, the use of very large boulders for the walls of the houses, the vicinity of Hafit and Umm an-Nar tombs as well as the complete absence of pottery make it probable that these structures constitute a Hafit or very early Umm an-Nar settlement. However, only excavations could confirm this sup-position.

The survey in the oasis of Ibra’ shows that there has been a continuous use of that area over the last five millennia. The settlement areas are situated close to the wadi but their position shifted with the time. The reasons for this shift will have to be investigated. In all cases the settlements were small. An extension of the oasis was only possible by the intensification of falaj constructions, which enlarged the agricultural basis. This was supported by the Ya‘ariba dynasty in the seventeenth century.